Learning Economics in World of Warcraft

Licensed Creative Commons, share alike, non commercial, by attribution

Abstract

World of Warcraft is an online computer game with 10 million subscribers (as at June 08). It has an ingame free market economy which allows for market research and the teaching of economic theory by hands on activities. This paper describes how the ingame auction house could be used to teach economic theory with hands on activities to explore the relationship between supply, demand and price.

About the game

World of Warcraft (commonly known as WoW) is a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG). People control a character avatar within a persistent game world, exploring the landscape, fighting monsters, performing quests, building skills, and interacting with NPCs, as well as other players. The game rewards success with in-game money, items, experience and reputation, all of which in turn allow players to improve their skill and power. Players can level up their characters from level one to the next.

World of Warcraft uses server clusters (known as "realms") to allow players to choose their preferred gameplay type and to allow the game to support as many subscribers as it does. There are four types of realms: Normal (also known as PvE or player versus environment), PvP (player versus player), RP (a roleplaying Normal/PvE server) and RP-PvP (roleplaying PvP server):

When creating a character in World of Warcraft, the player can choose from ten different races in two factions: Alliance and Horde. Race determines the character's appearance, starting location, and initial skill set, called "racial traits".

* The Alliance currently consists of Humans, Night Elves, Dwarfs, Gnomes and Draenei.

* The Horde currently consists of Orcs, Tauren, Undead, Trolls and Blood Elves.

The game has nine character classes that a player can choose from, though not all classes are available for each race. During the course of playing the game, players may choose to develop side skills for their character(s). These non-combat skills are called professions.

To play, there is an initial purchase price and a monthly fee as shown below

Suggested Retail Price Monthly Fee

Europe E14.99 E11-E13

United Kingdom £9.99 £7.70-£9

North America/Oceania US$20 $13-$15

Video game stores commonly stock the trial version of World of Warcraft in DVD form priced at A$2 or \2 including VAT, which include the game and 14 days of gameplay.

Derived from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_of_warcraft (retrieved 30/4/08)

About in game trading

To be able to trade effectively, it is estimated that the character would need to be levelled up to level 10. The trial version may not allow enough time for this, it is also uncertain whether the trial version has the full functionality including the ability to use the auction house.

Estimated playing time to reach various levels is shown below.

Level 10, 4 hours playing time

Level 25, 25 hours playing time

Level 55 200 hours playing time

WoW has 10 million subscribers and has a market economy where in game items can be traded for in game currency. There are approximately 150 independent servers or realms, so within one realm there is a market economy of approximately 70,000 players. Goods are traded at an auction house with market forces determining prices. This makes WoW an ideal testbed for testing economic theories of free market behaviour.

Tradeable goods are best achieved through the professions. For example, with professions of herbalism and alchemy, the trader can collect herbs (known as materials or mats) and transform them into potions (pots). There is a market for both the materials and the potions. For example, the player could search for Mageroyal and Stranglekelp and either transform them into Lesser Mana Potion which could be traded or just trade the materials direct. You will find the online database www.thottbot.com invaluable in helping level up and finding materials.

Alternative professions such as mining and engineering may be better, players suggest that mining ores such as copper give easy access to tradeable commodities

The player is able to test theories of supply and demand and influence market prices by trading on the open market.

Activities:

Discuss, how well does the market mirror the real world?

What determines the supply of money?

Is there any equivalent to monetary and fiscal interventions which are practised in real economies?

If you were Blizzard (the makers of WoW) what market interventions might you do?

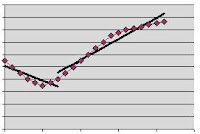

Observe long term price trends e.g. at http://www.wowecon.com

Is there any long term inflationary or deflationary trend?

Observe the trading history of some commodity which you could trade. Can you estimate the elasticity of supply and demand.

Having estimated market elasticity, predict the effect of your trade on the market.

Do a large amount of trading of one commodity. Are the price effects what you predicted? If not, why?

Classic market theory works on the assumption that the market is perfectly informed. How well informed is the market?

How is the market informed?

Are there delayed effects as the market adjusts? What do you think the mechanism is?

Useful references

www.thottbot.com invaluable in helping level up and finding materials

http://www.wowecon.com/ market information and statistics

http://www.warcraftriches.com/ Derek's Gold Mastery Guide

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=peR8Hs9s_wY “

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6PDRLnmCLyQ World of Warcraft Gold Farm be Rich (auction house)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2jDVsFVXE0 World of Warcraft auction house

Sample trades

I am told that for most items, they are sold at the buyout price, rather than the auction price. The item chosen for trade was Stranglekelp. It was commanding a good price at auction.

Typical WoW wide prices were listed at www.wowecon.com at 20s to 30 s. (100 copper = 1 silver, 100 silver = 1 gold)

The auction house listed 19 units for sale at 21s to 173s I had no information as to whether it was actually selling at these prices or in what volumes. I listed at a number of units at a range of prices.

| Date | Bought | Sold |

|---|---|---|

| 20 May | | 3 @ 16s |

| | | 3 @ 30 |

| | | 3 @ 33 |

| | | 6 @ 40 |

| | | 5 @ 51 |

| | | 10 @ 52 |

| | | 5 @ 54 |

| 21 May | | 25 @ 53 |

| | | 10 @ 80 |

| | | 10 @ 100s |

At this stage I realised that Stranglekelp was selling as high as 153s for a patient seller and my cheaper sales were being bought and immediately relisted at a higher price.

| Date | Bought | Sold |

|---|---|---|

| 22 May | 11 @ 11s | 90 @ 100 |

| 23 May | 6 @ 80 | 40 @ 100 |

| | 20 @ 21 | 60 @ 100 |

| | 12 @ 91 | |

| | 20 @ 95 | |

| | 4 @ 60 | 4 @ 125 |

| 26 May | | 100 @ 1.00 |

| 29 May | 74 @ 40 | 148 @ 100 |

| 2 June | 19 @ 75 | 20 @ 100 |

| | 95 @ 50 | |

I adopted this strategy and was able to maintain a market price of 100s per Stranglekelp and sell most if not all the market volume. The volume was approximately 460 units in 11 days or 40 units a day. The market seemed to be unresponsive to price. Purchasers would buy at any price so that high priced stock would eventually clear when no cheaper stock was available. Sellers would sell much more cheaply than the market could support.